Greenland Review | Movie

Clarke, a recently discovered comet composed of many fragments of rock, is due to fly past Earth. But when a chunk of rock slams into a major city, destroying it instantly, it becomes clear that Earth is about to have a very bad day. As is structural engineer John Garrity (Gerard Butler), who finds that he and his family have been selected to seek shelter in an underground bunker. Getting there, however, will be far from easy…

By now, we’ve all got enough of a handle on Gerard Butler’s pulpy, testosterone-fuelled, B-movie output that we know, with absolute certainty, what a movie in which he faces off against a planet-killing comet will look like. Geostorm 2.0, right? In which our gruff hero absolutely chins the living hell out of a flying piece of space-rock before kicking it down a well with the rejoinder, “THIS! IS! EARTH!” Happily, Greenland is a very different proposition — and, perhaps surprisingly, a much better one.

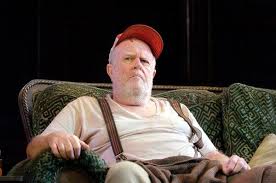

Reteaming with his Angel Has Fallen director Ric Roman Waugh, Greenland is interesting for a number of reasons, not least of which is its determination to treat the death of the world by solid rock with rock-solid verisimilitude. And if that means that it’s time to park the OTT heroics for a man who usually trades almost exclusively in OTT heroism, then so be it. Less a case of The Butler Did It, more What The Butler Saw, Waugh and writer Chris Sparling are happy to place Butler at the fringes of cosmic events so big that there’s very little he can do except look on, and try to stay alive. This is a movie about a desperate struggle for survival, not one-liners and headbutts. An action set-piece in Greenland means a man running back to his car to fetch something left behind. Okay, there’s a bit where Butler’s John Garrity faces off against two guys, armed only with a hammer, but the movie makes it very clear that, for once, he has absolutely no clue what he’s doing. There’s something in Butler’s eyes throughout that we haven’t seen very often in his work: fear.

That’s as a result of the decision to eschew the multi-character approach, and the bombastic, apocalypse porn of previous killer-comet movies like 1998’s double whammy of Deep Impact and Armageddon (okay, asteroid in the latter). If you’re looking for a Roland Emmerich-style wallow in the destruction of major cities, move on, pal. Waugh correctly guesses that we’ve had enough of watching CG waves (either of water or fire) smash into skyscrapers. When those bits do come, they’re glimpsed as part of news reports, rather than as sequences in their own right.

The opening half-hour feels absolutely plausible, and absolutely horrifying.

Instead, Waugh and Sparling go down the same road Spielberg travelled with War Of The Worlds, focusing entirely on Garrity’s day; one that begins with him going about his business, with barely a care in the world (other than, of course, a very fraught marital situation back at home, with a wife who no longer trusts him), and ends with humanity suddenly very aware that the comet, Clarke, which was meant to harmlessly sail past Earth, is instead going to give it a million-degree makeover.

The opening half-hour, in which Waugh’s relentlessly urgent and roving camera tracks Butler as the full horror of the situation dawns on him, and everyone else around him, feels absolutely plausible, and absolutely horrifying. Vast convoys of planes in the sky act as portents; government text messages meant for him, and him only (as a structural engineer, he’s a man whose particular set of skills would be in demand to help rebuild any post-impact society), come at the worst possible time, sending his neighbours into paroxysms of panic; the roads quickly gnarl up as people pile into their cars to try to escape the inescapable.

Once the Garritys hit the road, the film begins to feel like the last 20 minutes of Miracle Mile, in which society crumbles in double-quick time. Things quickly go wrong for the Garritys, which allows Morena Baccarin a chance to shine as a mother overcome with terror, and as they both set about overcoming all manner of adversity, they encounter the best and worst of humanity in double-quick time. It’s a talkier, more philosophical movie than you might have expected, with the emphasis on character throughout. But, even though the tone is serious, this isn’t ‘Threads Part II’ (you’ll be glad to hear), and there is a tendency to sprinkle one-damn-thing-after-another crises into the mix just to make sure you’re still awake. Which you will be — by focusing on the plight of one family, and with Butler the most engaging, vulnerable and downright human he’s been for a while, even if the film never quite matches the impact of that opening act, you’ll be tense all the way through to the impacts of the final act.

Butler’s best star vehicle in years, what could have been a bombastic bunch of boulders is, instead, a refreshingly clear-eyed and compelling affair. One of the best disaster movies in years.

United Kingdom

United Kingdom Argentina

Argentina  Australia

Australia  Austria

Austria  Brazil

Brazil  Canada

Canada  Germany

Germany  Ireland

Ireland  Italy

Italy  Malaysia

Malaysia  Mexico

Mexico  New Zealand

New Zealand  Poland

Poland  South Africa

South Africa  United States

United States